Adapted from a longer form essay of the same title, published in Music & Politics

I present here a Neo-Marxist theory of class and classical music. To help me with that, let me direct your attention to the classic 1949 short, Long-Haired Hare starring Bugs Bunny. Bugs has gotten into a feud with the operatic tenor Giovanni Jones. In the clip you’ll see Bugs exact his final revenge against Jones by seizing control of Jones’ concert soloing with an orchestra. Even seventy years later, the film captures realities and stereotypes of classical music, including the mythos of the conductor’s ability to control time and physical bodies. The source of Bugs’ power over Jones can be summed up in one word: class. By impersonating “Leopold,” (i.e. Leopold Stokowski) Bugs has entered into a social relation of domination—a class position—that grants him potential power over the labor of the orchestra and of Giovanni Jones. The humor comes from Bugs’ exploitation of this labor relation wherein he confronts and mocks Jones in his own sphere, classical music.

My talk invigorates musicology by providing a focused theorization of class. I take an important aspect of class—labor power —to provide clearer criteria for locating musicians in a class structure. This deviates from the usual recourse to Pierre Bourdieu’s theories about networking or consumption. Of course in life, to produce something usually requires consumption of something else. One cannot master the violin without consuming, in some manner, large amounts of music, recordings, buying a violin (or at least renting one), taking lessons, and otherwise acquiring all the materials required for violin playing. Even Bugs “Leopold” Bunny had to get his tuxedo (and earmuffs!) from somewhere. Here I focus on production to emphasize how the labor relations of classical music determine class, which better illuminates the power dynamics that shape the field.

What’s up (with classical music), Doc?

So what do I mean by “classical music” and what constitutes a “classical musician”? Classical music is not really one thing; rather, as Robert Walser has argued, it is a “hodgepodge” of various genres all assembled in particular ways in particular places toward particular goals. A consistent aspect of these practices, as Christopher Small and Lawrence Levine and Karen Alquist and many others have shown, is socioeconomic class and labor. Michael Roberts’ study of the American Federation of Musicians, for example, demonstrates how labor was a site of meaning and power. In the 1930s and 40s, the union purposefully excluded rock musicians through literacy requirements, which was part of broader struggles for class consciousness, taste, and control of musical labor markets.

I focus on classical music exclusively to better illuminate how it can function as part of a capitalist society. That is, after all, the type of society in which most people live. In a capitalist society, capitalist forms of production impact all spheres of life. A Neo-Marxist approach more properly understands classical music within the totality of a capitalist society. This is not to say that classical music is always a part of capital accumulation. Rather, it emphasizes that in capitalist societies the overwhelming majority of people, musicians included, must sell their labor power in order to earn money to buy the necessities for life. It also shows that classical music, myths about genius included, requires human labor power to exist.

What’s up (with class), Doc?

Class is a way of explaining hierarchies within a society. It is dynamic and changeable. As Erik Olin Wright has observed, class can be studied from three perspectives, subjectively, gradationally, and relationally. A subjective approach considers how people think of class for themselves. A “gradational” understanding of class is one wherein class is arranged like “rungs on a ladder.” Here, one measures class by comparing the assets and educational attainment of a person or group with some other person or group. The greater in value these are, the higher the “class” of the individual. Relational theories, according to Wright, investigate “the relationship of people to income-generating resources or assets”. A relational approach seeks to explain what causes material inequalities in the first place. It demonstrates why an employee must obey an employer, and why Jones and Bugs “Leopold” Bunny have different amounts power in their concert. In what follows, I focus on a relational approach because this is the approach least used in music scholarship, but the most useful for understanding the power relations of classical music labor.

What’s up, Doc(tor Marx)?

Karl Marx demonstrated that wage labor shapes the social relations and daily lives of anybody engaged in it. To summarize much of the argument in Capital, capitalist production has specifics that must be analyzed closely, but a capitalist society in general consists of the following social realities: 1. most people must sell their labor power in order to buy the necessities for life, 2. labor power is a special commodity because it produces more value than it costs to purchase, and 3. capitalists exploit labor in order to amass wealth. Marx’s analysis of class was relational, and differentiated between workers and capitalists via a simple equation, C-M-C vs M-C-M, which can help. If you sell your labor power as a commodity (C) to earn money (M) in order to buy commodities such as food to live (C), you’re in a working-class location. In contrast, if you use money (M) to throw commodities (C) into circulation in order to make more money (M’ in this case), you are a capitalist.

Most classical musicians are selling their labor in order to buy commodities necessary for living. They are not investing in factories, nor do they own the means of production such as scaled-up businesses that rely on exploiting the labor power of others. Many writers have framed musicians as “entrepreneurs.” This misrepresents the working relations of musicians. Such an account, for example, fails to explain why the tenor Jones must obey Bugs “Leopold” Bunny, not to mention why the members of the orchestra must sell their labor power in the first place. When musicians own their own small businesses, say as private teachers or as TV composers, they are, according to a Marxist analysis, in the same position as the petty bourgeoisie, small producers with very few (if any) employees. They are simply exploiting their own labor power.

“What’s up (with the middle class), Doc?”

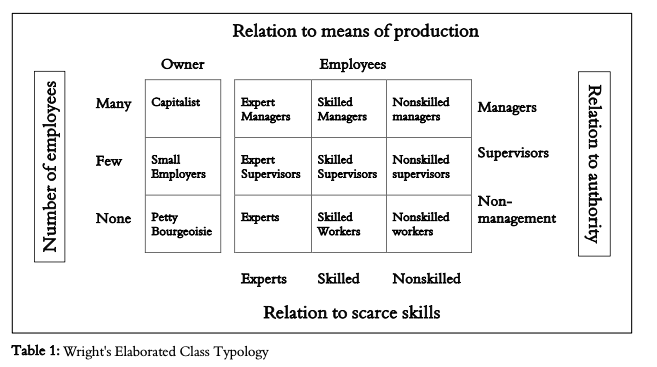

Erik Olin Wright, in his book Class Counts, built upon Marx’s work to distinguish between working and middle classes and between types of capitalists. Like Marx, Wright centered his analysis of class on exploitation. Bosses require workers for the creation of value while workers require bosses because they must sell their labor power in order to buy commodities to live. Where a strictly Marxist approach to class understands exploitation in terms of the appropriation of surplus, Wright adds “appropriation of effort.” This expands the analysis beyond strictly capitalist endeavors to include arts workers who are not obviously a part of capital accumulation. Bugs “Leopold” Bunny is definitely exploiting the effort of the other musicians, for example. Wright developed this table, which provides a relational analysis of class, based largely on daily working conditions. This helps map a person’s class location:

First it shows the individual’s relation to the means of production. The gap in the chart emphasizes the gulf in power between workers and those who own the means of production. Because most people do not own the means of production, they are automatically placed on the the right hand side of the divide in the chart.

Wright defined the “middle class” as people who didn’t own the means of production, but who still had authority over other workers. Authority addresses the ways that some people can be said to dominate others, from the ability to command behavior to the the ability to hire and fire. Employers, managers, and supervisors have enormous control over how people spend their time and effort, and many devote considerable energies toward surveilling workers to stimulate productivity. Wright described managers and supervisors as occupying “contradictory locations within class relations.” On the one hand, they had to sell their labor power to earn money to buy their livelihoods, on the other, they could share material interests with capitalists.

Wright’s third criteria that might located a person in the middle class were skills and expertise. People who had skills might be in a better position than the “nonskilled”, but only if those skills and expertise were somehow understood as valuable, somewhat rare, and if capitalists somehow could not easily access them. The rarity of skills could stem from perceived scarcity of innate talents of some kind or from control over access to skill development (such as seen in medical professions). Wright makes a point to argue that the principal criteria for a materialist analysis of class is a person’s location within exploitation relations, not simply their position of skills. Skill alone thus does not necessarily place someone in a middle-class position.

To summarize, the middle class should be understood as sellers of labor power who have shared interests with capitalists and who have authority over other workers. As people move up and to the left, they are in a more middle-class position and become increasingly aligned with the material interests of capitalists. As they move down and to the right, they are in more of a working-class position.

“What’s up (with class and classical music), Doc?”

This chart can be used to map out the class locations of classical musicians. Full-time classical musicians with a tenured job certainly possess skills perceived to be rare, and usually undergo training filled with barriers. They may also work in a union that controls access work. However, these facts alone do not automatically designate them as middle class. To be middle class in a relational analysis, they must enjoy somewhat significant workplace authority within exploitation relations, which usually come with material benefits. If they are simply experts who must sell their labor power, and if they lack authority in the workplace, as is the case of most orchestral musicians, they would be in the “skilled” or “experts” position in Wright’s chart. Accordingly, they are in a working-class location in the class structure.

Famous conductor

This understanding of class can be applied to conductors. Take the actual Leopold Stokowski when music director of the Philadelphia Symphony Orchestra. He would be an “expert manager” in Wright’s chart. Stokowski is in a contradictory location within class relations, specifically in a middle-class location when compared with the orchestra players, librarians, and other staff over whom he had authority. He would have authority in policy and hiring, close relations with the board, the ability to set most aspects of rehearsal schedules, and considerable autonomy in programming. At the same time, even famous conductors are also paid a wage by the institution, and they generally do not own the orchestra. Despite his relatively high levels of prestige, pay, autonomy, and authority, a conductor like “Stokowski” earns money from the sale of his labor power, just like any member of the working class. Were he to suffer some accident, perhaps one that severely impaired his arms, he could face major challenges in continuing to work (though his social network could likely be leveraged for support).

Chamber music

The class location of chamber musicians can also be mapped using this frame. For a full time solo-occupation group, the musicians are often workers who own the means of production. But owning a string trio is not the same as “owning” a regional symphony orchestra or a large film studio that hires musicians. These organizations have vast differences in terms of overall income, position in general capital production, number of employees, and economic impact. The chamber musicians are either petite bourgeoisie (few employees) or, if very successful, small employers. They have some authority in choosing repertoire and scheduling rehearsals, but they often have to negotiate repertoire with local vendors. Members themselves may also enjoy close relations with wealthy donors to fund individual projects directly. When compared with most orchestral musicians or freelance players, a full-time chamber music group is therefore in a more middle-class position, sharing the material interest of both capitalists (as small business owners and with the donors or capitalists who would hire them) and the working class (because they still rely on the sale of their labor power). This doesn’t really change if the chamber music group is a non-profit organization, as is true of many new music ensembles. In that case, depending on the structure of the organization, they may still have considerable authority while still relying on the sale of their labor-power to secure income.

“What’s up with subjectivity, Doc?

Understanding classical musicians as either working class or as petite bourgeoisie better accounts for the frustrations many classical musicians express all the time. Their material conditions don’t match their subjective sense of worth! That is, after all, why unions go on strike. One such study is Anna Bull’s recent book on adolescent classical music ensembles. In it, she successfully demonstrates how class—in gradational, subjective, and relational terms—informs young people’s music educational experiences. To be clear, a relational analysis may not agree with the class subjectivity of all classical musicians all the time. But accounting for class locations must be about more than simply asking people how they feel about work. We must confirm whether what people say matches what they do and where their money comes from. Unless they can imitate a famous conductor and seize control of an orchestra like Bugs Bunny, real people remain enmeshed within the classed relations of classical music and capitalist societies.

Conclusion

Analyzing class ought to account for labor conditions and working relations. This approach usefully expands upon Marx by maintaining a focus on the compulsion toward wage labor that most of us live with. It demonstrates work as a structuring aspect of people’s lives (including musicians). It also provides a way to critique individual understandings of class by contrasting what people believe to be true with the classed relations that shape their lives. A Neo-Marxist approach situates classical music within the totality of a capitalist society.

Cartoon tenor Giovanni Jones is only as powerful as his work relations permit, a weakness fully exploited by Bugs “Leopold” Bunny. Bugs’ power over Jones demonstrates comically what I have outlined in more academic terms. Both show where classical music gains some of its power: from the labor power and class locations of those who produce it. Scholars such as Marianna Ritchey, Bryan Pankhurst, Stephan Hammel, Timothy Taylor, Eric Drott, Anna Bull and others have provided tools for engaging classical music within the capitalist totality. By putting class back into our studies of classical music, we can gain a fuller picture of what it means to create, consume, teach, and enjoy classical music, one that does not shy away from hard questions, troubling relations, or even from the comedic pranks of a rascally rabbit.